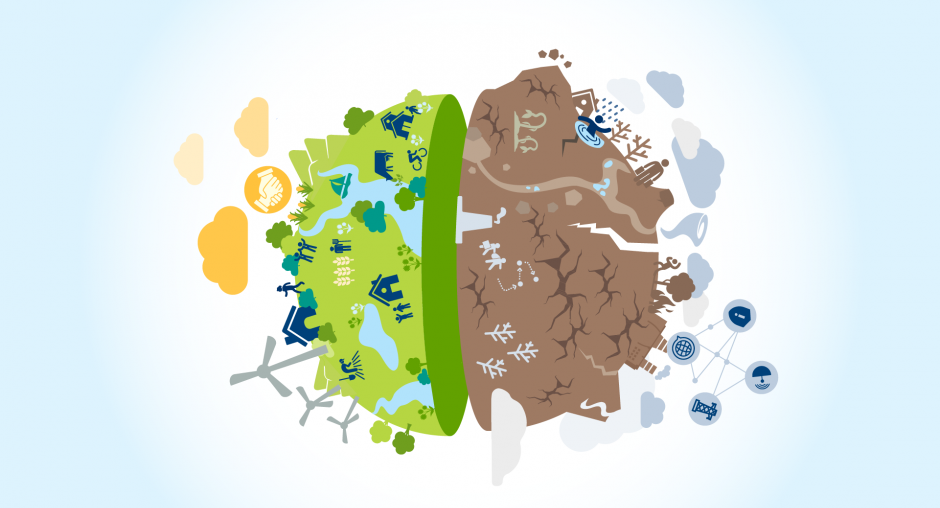

The greenhouse gases emitted by the automotive industry are mostly caused by the very vehicles that the industry has sold over the past decades. Estimates range from 75% to 96%. But making a car also pollutes. The decarbonization of the production of cars and auto parts involves Brazil, as the factories installed in the country must report to their headquarters, which have global targets to meet. Neutralizing the carbon emitted by the entire chain that involves a vehicle – which includes 2,500 to 5,000 parts – is a complex task. Even with a giant challenge ahead, the industry is already starting to move forward.

As a way to show society that they care about the climate emergency, the largest companies in the sector have started to work with deadlines that move up by at least ten years the goal of the Paris Agreement, which establishes the neutrality of carbon emissions by 2050.

Decarbonization comes at a price. Jaime Ardila, founder of U.S.-based Hawksbill and a consultant in this field, recalled that investments unveiled to this end around the world total $200 billion, according to international studies, a figure that excludes the electrification of vehicles. “But, in the end, the investments will have to be larger,” he said.

In Brazil, there are no calculations of how much the automotive industry has invested in the decarbonization of its industrial processes and logistics. “It depends on the paths that each one will follow,” said Masao Ukon, a partner at Boston Consulting Group. If an auto parts company exchanges the entire fleet that transports its products for electric trucks, for example, it will spend more.

The sector’s great dilemma is how to find ways to involve the whole chain, as hundreds of suppliers deliver thousands of components daily. This is a system without stocks, a condition familiar to the industry for decades. If, on the one hand, just-in-time production has become a reference of lean manufacturing, on the other hand, the method consists of a daily shuttle of trucks to transport the parts.

For the carbon neutralization in this sector to be complete, it must also include car haulers, which take vehicles to dealerships and ports across the country. Among suppliers, the purchasing teams of the automakers have been instructed to include as selection criteria companies that stand out in sustainable practices, in addition to ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance) principles.

Scania has created a logistics laboratory that monitors the parts transportation routes. Guilherme Garbin, the company’s maintenance manager, said that this center helps truck drivers choose less congested routes and take advantage of the space in the trailers for maximum load occupancy. “It’s a constant learning process.”

Inside the vehicle factories, the picture is less complex. Brazil has the advantage of using hydroelectric energy, which gives these companies points in the global decarbonization race. Factories located in countries with low supply of renewable power sources have tighter targets. This lightens the burden on the Brazilian subsidiaries on the one hand. On the other hand, the water crisis has triggered warnings. Solar power panels are already in part of the factories of General Motors in São Caetano do Sul, São Paulo, and of Mercedes-Benz in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais. Iochpe Maxion, a Brazilian wheel manufacturer that has become a multinational, includes overseas plants to close its decarbonization account. The company’s line in Thailand already operates partly with solar power.

Iochpe, the world’s largest wheel maker, also has an example of how modifying products based on changing consumer – and industry – habits can help reduce emissions. The company realized that the production of aluminum wheels emits more than three times as much carbon dioxide as the same product made of steel. There are 9 kilograms of CO2 in every kilogram of aluminum wheels, versus 2.3 in steel wheels. The challenge is to offer alternatives or change the habit of consumers who see the sophisticated finishing of aluminum wheels as a consumption dream.

Another similar example comes from U.S.-based Cummins, which used to paint the engines it delivered to heavy equipment manufacturers, such as trucks. “We started to send engines without color, only with varnish, to customers,” said Adriano Rishi, the company’s CEO for Brazil. Nobody complained.

Not all changes, therefore, require high investments. Some ideas are simple and cost little or nothing. “We can stop painting more hidden parts in a car,” said Antonio Filosa, the chief operating officer of Stellantis for South America. The search for lighter materials has also helped, according to Iochpe Maxion CEO Marcos de Oliveira.

The challenge also involves reducing power and water consumption. Between 2003 and 2019, General Motors managed to reduce by 60% the electricity consumption per vehicle and by 2030 it intends to save 35% of the power spent in processes compared with 2010, according to Glaucia Roveri, GM South America’s energy, environment and sustainability manager.

Older plants have been adjusted. With more than 90 years, GM’s facilities in São Caetano do Sul, São Paulo, recently had the press system replaced by more modern technology, which reduced power consumption by 50%, Ms. Roveri said. Because it was located in the city at a time when the region was not very urbanized, this was one of the first factories, at the end of the 1980s, to install a water treatment system for industrial reuse. “Today, we are all living around the factories. People are going to start rejecting products from companies that are not environmentally correct,” she said.

Mercedes-Benz’s plant in São Bernardo, which started operating in 1956, has been receiving equipment that use less electricity and smart lighting systems. “We are in this transformation process since 2018,” said Rafael Gazi, the company’s process planning manager.

ZF, the German auto parts giant, has also adapted its Brazilian facility. According to the regional environmental manager, Celso Guerra, in addition to the exchange of engines and compressors, the company adopted power efficiency modules for the total shutdown or the secondary functions of the machines.

In newer factories, designed with greener solutions, the process is easier. A year ago, Stellantis announced that its plant in Goiana, Pernambuco, achieved carbon neutrality. The vehicle factory had already obtained, in 2017, the gold seal of the GHG Protocol Brasil program, which seeks to encourage companies to quantify and manage greenhouse gas emissions. By 2021, all 16 factories that make up the supplier complex were included. Toyota’s Sorocaba plant, in the São Paulo state, is about to achieve carbon neutrality. The company is, however, waiting for an audit result, said Viviane Mansi, head of sustainability for Latin America.

Waste disposal is another problem in industrial processes. Thanks to the recovery of packaging and better use of organic waste (such as food scraps consumed in the cafeterias, which serve as fertilizer for the gardens) Scania reduced the portion of waste sent to landfills to 6% from 14% in three years. “Our goal is to reach zero,” Mr. Garbin said. The company will soon start its own sewage treatment plant around its plant in São Bernardo.

In vehicle factories, painting is among the activities that demand the most electricity for the process and water for cleaning the equipment when changing colors. The team at Mercedes’ truck cab plant in Juiz de Fora has discovered a new way to clean the supports that carry parts during the painting process. A simple solvent will replace the thousands of liters of water that used to be sprayed when cleaning the parts.

Next to the factory building was an unused shed. There, the company now stores tanks with solvent where the parts are immersed. This is a sustainable process, said Marcos Marsola, process planning manager in Juiz de Fora. The solvent can be reused in the same process. And the leftover paint goes to the cement industry. To complete the process, the roof of the shed received solar power panels. Mr. Marsola even looked for international benchmark, but he couldn’t find any. “This project started from scratch,” he said.

In quality and safety tests of cars, the industry is beginning to replace part of the so-called “crash tests” (in which the vehicles are destroyed) by virtual simulations. This is done by Volks’s engineering team in São Bernardo, for example. Recently, Stellantis invested in a laboratory in the Betim plant that does from material analysis to the final product testing. “The crash test also pollutes as we often sent the cars for tests abroad, which involved diesel consumption in trucks and ships,” Mr. Filosa said. In this case, decarbonizing also helps companies reduce costs.

Financial operations are also starting to be part of decarbonization. At the beginning of the month, Volkswagen reached an agreement with Bradesco to raise debt with ESG commitments. In exchange for funds, the automaker commits to transfer 12% of its CO2 emissions in the production process from fossil to biogenic origin by 2024, and to increase the share of biomethane to 20% of the total gas used by the factories.

New ideas even include employee transport. Volvo intends to reduce CO2 emissions by 30% in employee transport by 2025. According to the company’s CEO, Wilson Lirmann, this involves chartered buses at the Curitiba plant and even remote working. “This is something that the pandemic taught us,” he said. Scania created, for employees who use fleet cars, a corporate card that only allows them to fill up with ethanol.

Despite the several efforts, for the time being, decarbonization plans in this sector have proven to be less organized than its historical and impeccable industrial production system. Companies acknowledge, however, the need to adapt not only the vehicles but also the chain that produces them to the climate urgency. “It’s a matter of survival,” Mr. Garbin said.

Source: Valor International